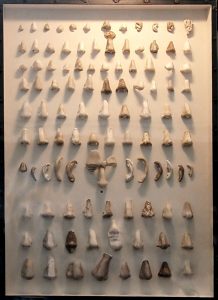

In a Copenhagen sculpture museum, hundreds of noses hang on a wall. The plaster noses were once pasted by conservators onto mutilated statues from antiquity, but were later removed. Today, the loose noses form a kind of “nose pharmacy. In Denmark, one therefore speaks of the nasothek.

In ancient times, statues were regularly deliberately damaged, for example, when an emperor or dignitary had fallen from grace or a previously venerated god was suddenly considered “pagan”. It was not always necessary to destroy the entire statue. Sometimes mutilation was sufficient and the statues were only “de-nudged”. In the very readable and entertaining book A Small Cultural History of the (Big) Nose by Caro Verbeek, one can read why anger was vented precisely on noses:

“Statues were thought at the time to have some kind of divine life force thanks to their nose. After all, we breathe through this part of the body. According to Egyptologist Adela Oppenheim of the Metropolitan Art Museum in New York, grave robbers therefore saw fit to “kill” statues by cutting off their noses. This way the thieves could go about their business in peace without the piercing glances of gods.”

Fashion

One place where many new noses were placed is the Ny Glyptotek, a museum in Denmark’s capital, Copenhagen, founded by wealthy brewer Carl Jacobsen. For decades, a large number of Greek and Roman sculptures that had once been mutilated could be admired here again with noses. But today that is no longer possible. In fact, the sculptures have lost their noses again. Not because a visitor smashed the olfactory organs away with a hammer, but simply because fashion changed after World War II. Conservators felt that it was better to show the statues in their original state and thus came to the conclusion that it was better to reverse the nineteenth century adjustment. One by one, the noses were removed as a result. Discarded they were not. Today, hundreds of removed noses can be admired in the so-called “nasothek”. Handy in case people change their minds again in a few decades.

By the way, not all noses were removed. In some cases it was decided to leave the artificial noses in place, for fear that the statues would collapse if removed.

Lund University in Sweden also has its own “nose pharmacy.