From Camp Westerbork in the dutch province Drenthe War more than 100,000 Jews living in the Netherlands Jews and 245 Roma were during the Second World deported by train to concentration and extermination camps in Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic. Today, a memorial center can be found near the former camp site. The history of Camp Westerbork in a nutshell.

The government barely provided care to the refugees who had entered the country. The support that the emigrated Jews received came mainly through private initiatives. Until the start of the war, a total of some 10,000 German refugees were eventually admitted.

The government decided to build a central camp for these refugees. Initially, the eye fell on a site around Elspeet in the Veluwe, but due to protests that camp was not built. Queen Wilhelmina ‘s protest in particular weighed heavily. The queen was not waiting for a camp so close to Paleis Het Loo in Apeldoorn.

Eventually a lot further east, near Westerbork in Drenthe, a site was found where the Central Refugee Camp could be built. Money for the construction had to be largely coughed up by the Jewish community in the Netherlands.

The beginning of Camp Westerbork

The first 22 refugees arrived at the camp on October 9, 1939. At that time there were only barracks. Werner Bloch, one of the first residents, describes on the website of the Camp Westerbork Memorial Center what he saw when he arrived in Drenthe:

“The further we got, the lonelier it got. At one point you only saw moors. Occasional bushes. And where the refugee camp would eventually come, was a huge expanse where only heather and sand were and which was very desolate.”

The first inhabitants had to work hard to make the area around the barracks somewhat habitable. It was not a storm. At the end of January 1940, the camp was inhabited by only 167 Jews. Only from February of that year did the flow of refugees really get going. By April 1940, Westerbork already had 749 refugees. Many of these Jews had come to the camp because they had been given a relatively good picture. In Camp Westerbork, for example, people would receive good education and there would be various recreational opportunities, but that was disappointing. There was a lot of hard work to be done in the remote camp on the rugged heathland.

WWII

Shortly after the German invasion, many Jews tried to flee the country. An evacuation plan had already been drawn up for this. The idea was to move to England via Zeeland. However, the Jews who left Westerbork had the misfortune that they did not get further than Zwolle by train, because the IJsselbrug had been blown up.

After the capitulation , the Dutch authorities decided to house all Jewish refugees in Westerbork. A completely different regime now reigned in the camp. From now on, walking in and out was no longer so easy and fifteen Marechaussees were appointed to supervise. The new commander, J. Schol, laid the foundations for a camp organization that was later taken over by the Germans. According to the Westerbork Memorial Center, Schol, who was certainly not pro-German, thought that a perfect organization was the best remedy to keep the Germans out for as long as possible. However, the German authorities were not at all pleased with the state of affairs in the camp:

“I have the impression that the Jews are treated far too humanely here and that, due to the attitude of the camp commander, the Jews feel very comfortable here. (…) It would be necessary above all to appoint another camp commander here.”

Schol eventually continued to work in the camp until January 1943, but from the summer of 1942 the camp leadership was in the hands of the Sicherheitspolizei (SD). In the meantime, numerous anti-Jewish measures had been introduced in the Netherlands.

Camp commander Gemmeker

What was special was that this Gemmeker was a real Nazi, but in Westerbork he mainly presented himself as a gentleman who usually also treated the prisoners very friendly. An eyewitness once summed up this behavior as follows:

“Gemmeker did not kick the Jews at Poland, but laughed at them at Poland.”

Transport

Gemmeker might act like a gentleman, but he saw it as his most important task to transport enough Jews to the east every week. And historians nowadays agree that the commander must have known what awaited the Jews there. A total of 93 trains departed from Westerbork camp for the camps in Eastern Europe, where in most cases destruction awaited. The first transport to Auschwitz took place on 15 and 16 July 1942. Usually two transports left a week, on Monday (later Tuesday) and Friday.

How many Jews had to be transported each week was decreed from Berlin. The SS men in Westerbork then passed on the numbers and dates to the camp organisation, which had been set up by German Jews. The actual preparation and execution of the transport was for the most part arranged by this camp leadership. Remembrance Center Camp Westerbork about the transports:

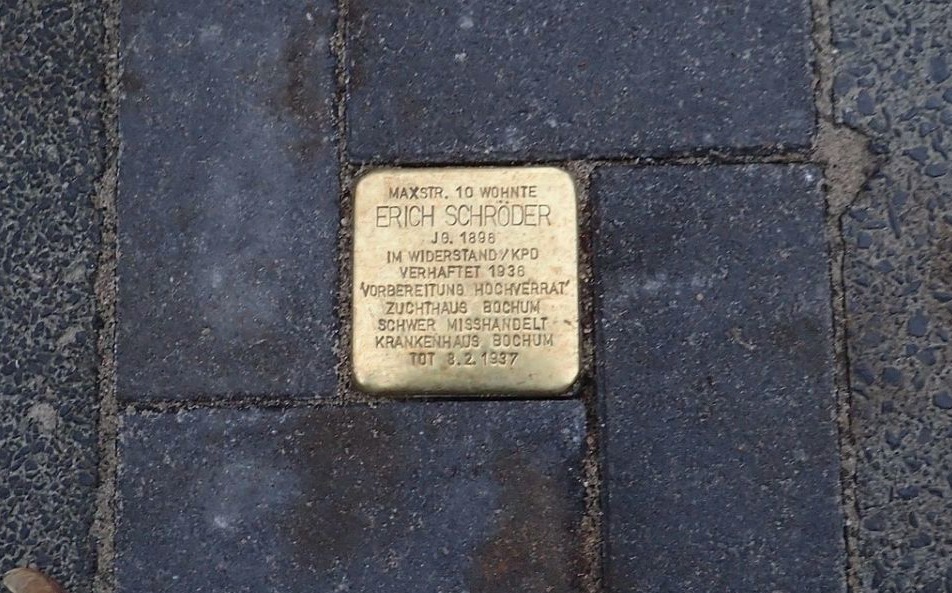

“The camp residents lived from ‘Tuesday to Tuesday’, from transport to transport. That lasted until September 13, 1944. Then the last train with 279 people left for Bergen-Belsen . Among them were 77 children who had been caught at their hiding places. Nearly 107,000 Jews had been deported to the East, mostly via Westerbork. In addition, 245 Sinti and Roma and a few dozen resistance fighters. Most trains went to Auschwitz. Other transports went to Sobibor, Theresienstadt and Bergen-Belsen. A much smaller number went to the Buchenwald and Ravensbrück camps . In total, only 5,000 people returned.”

Westerbork film

The fragment from the Westerbork film in which the Sinti girl Settela Steinbach looks at the viewer from a freight car has become an iconic image for the transports to Nazi death camps. The film can be viewed in its entirety here.

Liberation

On April 12, 1945, Camp Westerbork was liberated by Canadian soldiers. The complete liberation of the Netherlands, on 5 May of that year, was celebrated by many camp residents in the villa of the camp commander. This house still exists. It is one of the few surviving buildings in Westerbork.

After the liberation, the remaining 876 prisoners had to remain in the camp for some time, partly because the risk of the spread of infectious diseases was high. However, the watchtowers were manned from now on by members of the Dutch Interior Forces ,

After the war, the Dutch government used the camp for several years to house persecuted NSB members and other collaborators. This creates a strange situation. When the first NSB members are brought to the camp, several hundred Jews are still imprisoned there. A number of them are deployed during those first months of liberation to guard the internees.

In the early 1950s, Westerbork operated a repatriation camp for Indisch Dutch and from 1951 demobilized KNIL soldiers of South Moluccan descent were received. After this, almost all barracks were demolished and sold.

Memory

Today, the former camp site, which is open to visitors, houses several monuments, including the 102,000 Stone Monument, which commemorates the 102,000 Jews and Roma who were deported from the Netherlands during World War II and did not return. Since 2015, there are also two restored freight wagons on the site. The names and ages of the deportees can be heard in these wagons all year round.

The Westerbork National Monument is located where the railway ended. This important monument was designed by former prisoner Ralph Prins and was unveiled in 1970 by Queen Juliana . It consists of two upright, curled rails on 97 sleepers. These refer to the 93 transports from Westerbork and four transports from other locations in the country.